Friends, I need to tell you something. I used to be a person who feared zucchini season, who dreaded the part of the summer when CSA farm shares seem to be about 95% summer squash, who contemplated the feasibility of sneaking some extra zucchini onto neighbors’ porches under cover of darkness.

(“Oh!”, I’d imagine saying, if caught. “I figured you’d probably want some extra zucchini because you seem like the… sort of people… who’d… uh, who’d, uh want… uh… extra… zucchini…” and then, even in my imagination, I would trail off, the words hanging in the air like unwanted cucurbits hanging from a vine.)

I’ve changed.

I’ve become a zucchini fiend, desperate for my next fix, using all the zucchini from the CSA within a day of its arrival and then pining for the next batch. Jasmine and I ate five zucchinis as an appetizer the other day, and it’s all thanks to this recipe.

Googoots. Cucuzza, or cacuzza, or googootz. Whatever you call it, it’s amazing, and it uses up zucchini faster than anything I’ve ever seen. My friend Katie Fran taught me the recipe, straight out of her Italian-American heritage, and I’ve never been the same.

It’s a little hard to describe googoots, but imagine a melange of crispy zucchini slices, fresh garlic, the sharp tang of red wine vinegar or balsamic vinegar, and the heady aromas of basil and mint, all infused with the flavors of good olive oil and caramelization.

It’s a recipe that takes very little of your time and is ridiculously easy. I haven’t composted a single zucchini since learning to make this, and I’ve been considering asking neighbors if maybe they have any extra zucchini. Send help. (or send zucchini).

Making googoots

Start making googoots the day before you want to eat them, if you can, since roasting the zucchini goes better and faster if you’ve let them dry out first). Full recipe follows at the end of the post.

This is less a recipe than it is a cooking technique; as such, I’m not providing strict amounts. Taste frequently and adjust for the quantities you have. It’s a very forgiving recipe, too–I made one batch where I totally blackened the zucchini by accident, and the final product was still excellent. Cook boldly and without fear!

Take all the zucchini in the house, wash them, and trim off any bad spots. Kat says she sometimes uses eggplants, too. Yum!

Slice the zucchini as thinly as possible, making rounds. If you’re having trouble slicing, you’ll find that it goes easier if you flatten one side of the zucchini by cutting off a long stripe–then you can put that side against the cutting board, and the zucchini won’t roll around.

Lay a clean tea towel on a baking sheet. Lay the zucchini coins out on the sheet in a single layer, then sprinkle them lightly with salt. It’s okay if the coins overlap a bit.

Leave the cookie sheets of zucchini coins out, at room temperature, overnight. I’ve left them out for about 36 hours with no problems yet, so don’t worry too much about the timing. They’ll dry faster if you can put them in the path of a fan.

These slices aren’t particularly thin; I made the next batch with thinner slices because I wanted more caramelization. Whatever you do will be fine.

The next day…

Preheat the oven to 400º F (200º C/Gas Mark 6).

Slide the cookie sheet out from underneath the tea towel and drizzle it with olive oil.

Lay the zucchini coins out on the cookie sheet in a single layer. It’s okay if they overlap a little, so you shouldn’t need additional cookie sheets beyond the ones that had zucchini on them. Rub the coins around a little bit to make sure that the olive oil covers the whole baking sheet, then drizzle a little more oil over the top.

Bake at 400º F for 15 minutes, checking for browning after about 10 minutes. Stir the zucchini slices around a bit, and if they’re browning unevenly, try to put the more-browned bits in the center of the cookie sheets. Take the zucchini out when most of the pieces are browned and crispy around the edges.

I’ve noticed that different baking sheets cook at quite different speeds–the material makes a difference, as does the color. Just check occasionally and you’ll be fine.

And here’s your crispy summer squash, dramatically reduced in volume and already significantly more tasty than when you started:

Now we make it amazing.

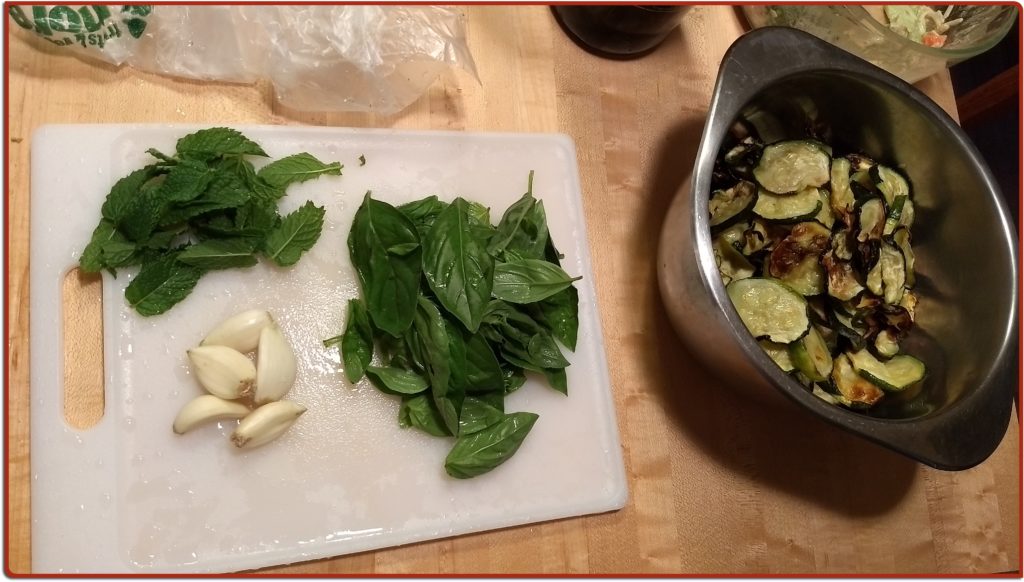

Tuck the zucchini slices into a bowl. Roughly chop some garlic and toss it in there. (I used 5 cloves of garlic with 5 zucchini for this batch, and it was lovely. Adjust for your preferences.)

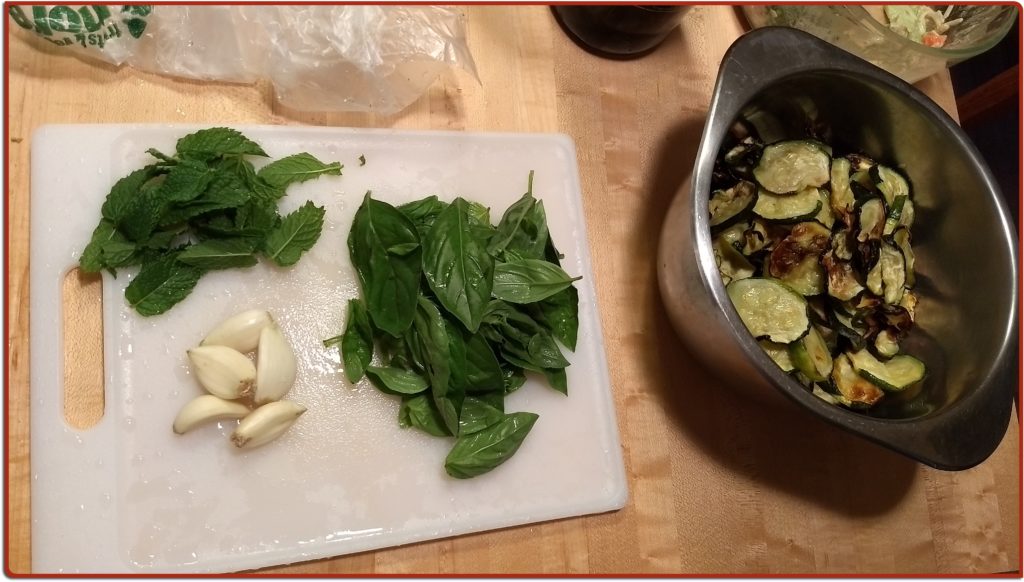

Wash and de-stem some basil (I used Genovese) and some mint (I used whatever mint grows in our yard). (bonus points if you use the fancy herbalist word for this process and call it garbling the basil and mint). Chop or tear the basil and mint and add them to the zucchini. (It’s fine to chiffonade the leaves if you feel like it, but it’s not necessary).

Stir the ingredients to mix them up a bit, and taste a bit to see how it’s coming along. Sprinkle some red wine vinegar or balsamic over the mixture, stirring frequently, and add some more olive oil.

You’re aiming for lightly moistening the zucchini without drowning it. If there’s liquid pooling at the bottom of the bowl, stop now–it’ll still be fine, and the zucchini will absorb it, but you probably want to use a bit less next time.

Add a bit of salt and pepper to taste, stir it some more, and you’re done. It’s good right away; it’s amazing the next day. I’m serious when I say that we’ve eaten 4-5 zucchinis worth of this stuff in a single sitting as an appetizer.

Anybody got some extra zucchini?

Googoots / Cucuzza (Caramelized Zucchini Salad)

From my friend Katie Fran, to whom I owe a great debt of gratitude for this recipe.

makes less than you want it to

- a bunch of zucchini, summer squash, courgettes, cucuzza, tromboncino, or other summer squash–eggplant is reputedly great, too

- good olive oil

- 4-8 cloves of garlic (try 1 clove per zucchini)

- red wine vinegar or balsamic vinegar

- a handful of fresh basil leaves

- a smaller handful of fresh mint leaves

- salt and pepper, to taste

- Wash and trim zucchini, removing any bad spots.

- Slice zucchini into thin coins. Cover a baking sheet with a tea towel, lay the coins out on it, and sprinkle with sea salt. Leave zucchini out to dry, at room temperature, overnight.

- Preheat oven to 400º F.

- Lightly coat a baking sheet with olive oil. Layer zucchini coins in a single layer on the sheet, drizzle with a bit more oil, and rub them around until they’re evenly coated.

- Bake approximately 15 minutes or until edges of coins are browned and crispy.

- Place zucchini coins in a bowl. Coarsely chop garlic, mint, and basil, adding them to the bowl. Stir.

- Add red wine vinegar or balsamic until coins are flavorful and lightly moistened. Drizzle a bit more olive oil in; stir. Add salt and pepper.

- Eat immediately or allow to marinate overnight in refrigerator.