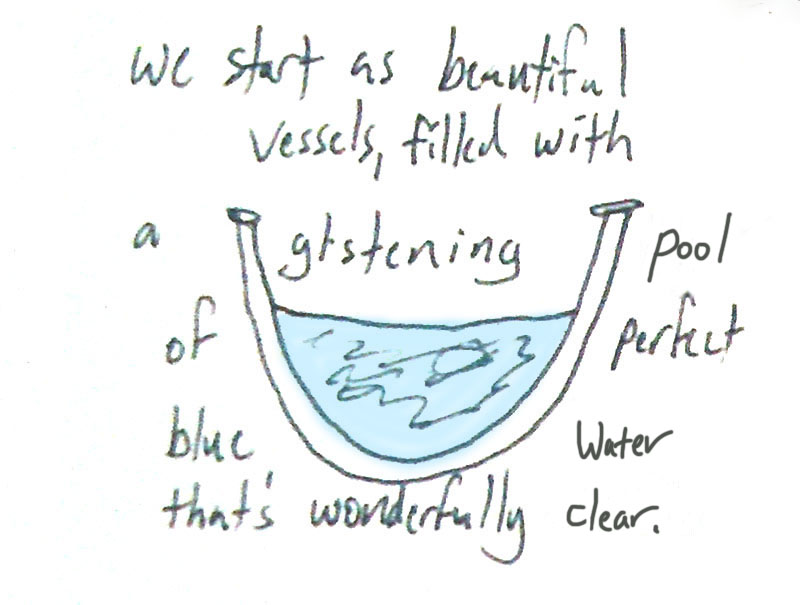

“Lived experience” basically just means “one actual person’s experiences”, and it stands apart from hypothetical experiences (existing only as conjecture), theories, and aggregate experiences (compiled from many people’s life experience). More and more fields are working to consciously acknowledge lived experience as valid and important, and I am thrilled about that because lived experience has been cast down in the weeds for a long time.

I’ve had a lot of people minimize or dismiss things that happened to me, and I’ve seen it happen to people I care about. I’ve had medical issues that got worse because a doctor didn’t believe me when I reported a problem. I’ve had friends whose stories of rape were dismissed because the accused was “a good guy” who “would never do something like that”.

I am sure that I’ve also dismissed people’s lived experience. I would like to do better in future. I’ve been thinking about how to deal with lived experience in a way that’s open, respectful, honest, and real, and this article is what came out.

It’s very easy to trample on people’s feelings when you’re talking about lived experience. A lot of discussions fall apart when people feel that their life stories have been dismissed.

The shortest guidelines

Don’t argue with people about what they experienced.

Listen respectfully, acknowledge it when their data points don’t fit your understanding, and don’t suppress their experiences just because they clash with your story. Don’t tell them what (you think) their experiences mean unless they ask you for that.

Be careful to distinguish in your head between facts and interpretations. Facts are objective truths about things that happen. Interpretations are the conclusions we draw about what those facts mean.

And really, don’t argue with people about what they experienced.

Simple facts

Start by assuming that people are telling the truth about the facts underlying their experiences.

Unless you have very strong affirmative evidence that their lived experience did not happen, you should give people the benefit of the doubt here. If you believe that their experience could not have happened, there’s a strong possibility that your beliefs are wrong.

Even if you disagree about the underlying facts, assume that they’re telling you the truth of what they felt and experienced.

I went to my doctor several years ago and said “I think I might have Lyme disease: I have all the symptoms on the diagnostic chart and I found an engorged tick biting my neck.” She told me “you can’t have Lyme disease—we don’t have it in NY”. In one sentence, she argued that my lived experience couldn’t be real because it conflicted with her beliefs. She argued with my facts and used her belief that a Lyme diagnosis was impossible (because we allegedly don’t have it in NY) to argue that my symptoms weren’t real and didn’t need treatment. (She didn’t ask whether I had recently traveled out of state, which I had, or where I thought I got the tick bite.)

My friend Eden says that we often reject others’ lived experiences because we simply don’t want them to be true. It’s painful to believe some of the things that happen to folks we care about, and it’s easy to slip into believing that their experiences couldn’t have happened simply because we wish they hadn’t. She also writes:

“In other cases, we dismiss because we do not want to recognize the reality of violence, oppression, evil, trauma in the world. We do not want bad things to happen in general–and certainly not to those we know and love. We need to believe that the world is a good and safe place not a broken and dangerous place, and coming in contact with others’ lived experiences often calls that belief/need into question.” — Eden Wales Freedman

When people insist that your lived experience didn’t happen or isn’t real, that’s often called silencing. My doctor silenced my experience by, essentially, arguing that it was impossible for my experience to be real.

Silencing can happen on lots of levels. If I tell you the story about my interaction with the doctor, I am reporting a fact to you. It actually happened—I was there! If you tell me that I’m wrong about that, whether because no doctor could be as [insert adjective] as that or because it shouldn’t have happened or whatever, you are also silencing my lived experience. Nobody likes that.

If you want a great cartoon explaining this, check out the always-fabulous Robot Hugs. And also this fabulous parallel-lives cartoon by Nate Swineheart.

Start by assuming that people are reporting their experiences truthfully, even if it seems far-fetched or unlikely to you.

Things to say:

- Would you tell me more about that?

- What was that like?

- How did that feel?

- I don’t think I understand yet—could you help me?

- I’m surprised to hear that, and it’s hard for me to believe. Could you tell me more so I can understand? (this one is less desirable because it starts with confrontation, but it’s better than nothing)

What do those facts mean?

We often run into trouble when we agree about what happened but disagree about what it means.

Suppose that you’ve been feeling really down for a long time and life doesn’t feel like it’s worth that much anymore. You see a billboard saying “Depressed? There’s help! See your doctor!” and decide to give it a shot, thinking maybe they can give you some antidepressants. The doctor sees you, tells you to exercise for 30 minutes every day and avoid eating anything with added sugar, and asks you to come in for a follow-up appointment in two weeks to see how things are going. You leave without the prescription you wanted.

You tell me your story while we’re hanging out later. I hear it and think “okay, that doctor has read some of the treatment guides that suggest exercise and food choices can be similarly effective compared to antidepressants, and carry fewer side effects, so she’s starting with the least-invasive treatment and then wants to check up on you in two weeks.”

You say “The doctor didn’t care at all—didn’t even seem to take it seriously. Just said ‘go work out and eat better’, as if that’s going to help anything. Bullshit.”

We agree about the facts—what was said—but not about what they mean.

If I jump right in and say “no, the doctor really does care, she’s just starting with a lower-intensity intervention to see if it will help”, I’m doing two things: I’m silencing your experience of being dismissed, and I’m assuming that I know what the fact pattern means. I’m also probably making you really angry. On some level, I’m silencing your lived experience and telling you that I know, better than you, what it all means.

Suppose a friend gets dumped and feels horrible about losing his soul mate. If my friend says “I’m never going to find anyone else”, is he correct? We agree on the facts of what already happened—the breakup—but perhaps we don’t agree on the conclusion that perpetual solitude is the only outcome.

There’s a place for disagreeing, but remember that my friend is still speaking of his lived experiences. Whether or not it’s true that he will never find anyone again, it’s true that that’s how he feels right now. If I attack his conclusions without establishing rapport and connecting first, he’s going to feel as though I’m out of touch or rude or uncaring.

Do your best to accept that people are reporting the facts, and their interpretation of those facts, accurately. If you disagree about the interpretation, do so respectfully, acknowledging that you are speaking about opinions rather than absolute truths.

Things to say:

- I hear you.

- Thank you for telling me about what this was like for you.

- Could you tell me more about how that felt?

- How does it feel to talk about this?

- It sounds like you think [interpretation] is the only answer to what happened. Did I get that right?

- I think I interpret that a little differently. May I share my thoughts?

- I agree about what happened, but I think I disagree about what it means. Could we talk about that?

What if the facts conflict?

It gets into grey area when you have strong evidence that the person’s lived experience is not factually correct. Start with making sure, for yourself, that you’re really talking about conflicting facts and not differing interpretations.

If you have a situation where a person is reporting something that objectively didn’t happen—say, a person reports that a therapist sexually assaulted them in the lobby, and the lobby was full of witnesses and a video camera that all agree no such thing occurred–it’s challenging to respect the person’s experience while rejecting the purported facts. It’s really tempting to just say “you’re wrong” and keep moving.

In some cases, that may still be the right choice. But if you want to continue having any kind of good relationship with the person, it may be better to say “I understand that that’s what you experienced, but that’s not what the rest of us saw.” Validating people’s experiences like this often de-escalates the conflict.

In my experience, it’s pretty rare for people to claim lived experience that is objectively untrue. Partly this is because speaking up for lived experience is intensely vulnerable and scary, and people tend not to fake it. So I’d like to encourage you to give people the benefit of the doubt as much as you can.

Things to say:

- I understand what you’ve said, but I saw it differently. Can I tell you what I saw?

- I hear what you’re saying, and I need to share some things I saw.

- It seems like we experienced different things. Could we talk about that?

- I’m struggling to understand what you said, because I experienced something totally different. Could we talk about the differences and figure it out together?

Lived experience versus hypotheses

In my scientific training, I was taught that it only takes a single piece of data to disprove a hypothesis, and that conjectures and belief structures only become strong when, over and over again, they survive all attempts to disprove them. If anyone presents valid evidence that conflicts, the hypothesis is wrong.

I’d like us to adopt this way of thinking about lived experience when we’re talking about medicine, about violence, about mental health, about oppression, about suicide, and about the other kinds of lived experience people bring up.

If we believe that our college campus is free of sexual assault and a woman shows up saying she was raped, we’re presenting a belief and she’s presenting a fact. Unless we can prove that her fact is invalid or untrue, our belief is wrong. End of story.

If my doctor tells me that we don’t have Lyme disease in NY and I present a tick, in NY, that’s carrying Lyme disease, she’s presenting a belief and I am presenting a fact. Unless she can prove that my fact is invalid or untrue, her belief is wrong. End of story.

If a suicidal person tells you life isn’t worth living anymore, and you believe that suicide is a sin and that life is infinitely precious, you’re both presenting beliefs. Your belief is valid for you; her belief is valid for her. You don’t get to argue that she’s wrong. You can respectfully offer a different interpretation, but that’s different from saying she’s wrong.

Partnership

I’ve framed much of this discussion in an adversarial way, because that’s how a lot of people approach the lived experience topic: there are people with high-level understanding of how things work, and there are people with lived experience, and never the twain shall meet.

Sometimes, disagreements arise simply because the square pegs of lived experience don’t fit into the round holes of expectations. Sometimes this is a big deal, like my experience with a doctor who didn’t believe me about being bitten by a tick. That disagreement has cost me thousands of dollars in medical bills, a lot of pain, and a ton of Lyme-related disabilities that are arguably caused by my doctor withholding the early treatment I asked for.

But other times, people dismiss lived experience casually, without even thinking about it. I have a ton of allergies, and some of the worst ones are to dogs and perfumes. People often hear about the dog one and say “Really? But you have a cat!”. I say “yep. Not allergic to cats”. Often, they respond “most people are allergic to cats and not allergic to dogs. Are you sure you don’t have it backwards?”. This is small, but it’s still dismissing lived experience.

Or I’ll talk about the perfume allergy, which is severe enough that I often get migraines for days and asthma attacks that leave me gasping for air as I scramble to find my inhaler. And that’s just what happens from being around people wearing perfume—let’s not talk about what happens when people hug me or spray me with it. When I talk about this, people often say “oh, but it’s hypoallergenic!” or “well, I only used a little” or “it’s very mild”. Do you see how these comments dismiss my lived experience in favor of a theory about what should have happened? The theory is that this perfume is hypoallergenic, and my experience is that now I can’t breathe and am losing the vision in my left eye because of a migraine.

I’m using the term “theorists” as a catch-all phrase for people who argue against lived experience on the basis of assumptions, beliefs, or anything else that isn’t purely a fact. I’m obviously talking about research communities, but I’m also talking about how we live our daily lives.

When we tell our daughters “oh, he just has a crush on you” when they report that a boy is touching them or making them uncomfortable, we are silencing lived experience. When the boss screams at a coworker and we try to comfort him by saying “oh, I’m sure she didn’t mean anything by it”, we are dismissing lived experience. In each of these situations, we’re acting as theorists, pitting our beliefs against the facts of other people’s lives. I’d like us to stop doing it.

Often these fights are really bitter, because the theorists feel like the lived experience people are just insisting on having their own anecdotes—most of which are outliers—heard, and it’s messing up the data or just being a pain to live with. And the lived experience people feel that the theorists are ignoring real experiences in order to have simpler models, cleaner datasets, and a life free of needing to care about others. There’s a lot of disrespect on both sides.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. The suicide prevention movement offers a good example of how established groups are working to incorporate the voices of people with lived experience—in this case, suicide attempt survivors and suicide loss survivors—so we can do a better job of protecting people against suicide.

We are stronger when we respect and learn from lived experience, and when we use it to nourish deeper understanding and to build better systems. It starts with listening to people with lived experience, asking good questions, and respecting the answers.

(I am grateful to Dr. Eden Wales Freedman, Dese’Rae Stage, Dr. April Foreman, Dr. Laurel K, and Karen Easter for reading and commenting on the earlier drafts of this post. Thanks, team!)

I’m gonna just go ahead and quote that (emphasis mine):

I’m gonna just go ahead and quote that (emphasis mine):