You’ve still got plenty of time to make yourself some dandelion tincture before the snows fly. Although it’s best to catch dandelions when they’re flowering so you get those tasty flowers into the mix, it’s fine to make the tincture without them.

In late August and early September here in northern NY, there are still plenty of healthy dandelions to be found. So let’s get looking!

How to identify dandelions

Dandelions, French for dents-de-lion or lions’ teeth, have several characteristics that help you identify them. You need to see all of these to have a positive ID.

- Large, dark green leaves with toothed or lobed edges. They sort of look like someone took a plain leaf and cut teeth into it with pinking shears. If it’s a straight edge, it’s probably not a dandelion.

- A basal rosette. That means a bunch of leaves and things issuing from a central point and radiating outward from it in all directions.

- If flowers are present, they are bright yellow with lots of short, straight petals. The key point is the flower stem: it is thick, hollow, breaks easily, and exudes a whitish sap when broken. Usually the stems have a reddish or purplish shade, at least around here.

- If you dig up the plant, does it have a taproot? That’s a thick, long, central root that plunges deep into the soil.

If your prospective plant doesn’t fit these guidelines, don’t use it.

Dandelion or not?

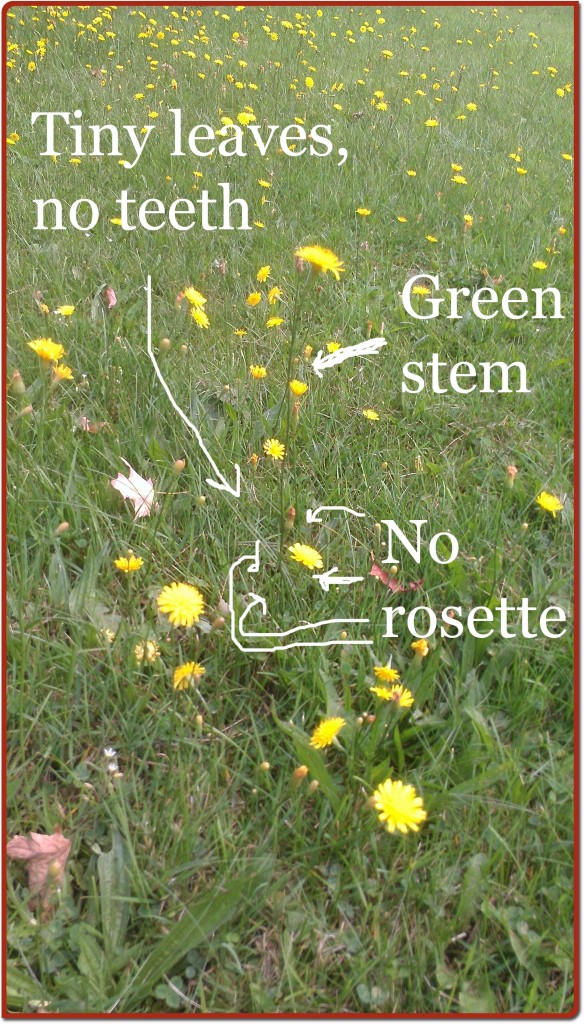

Are these dandelions?

Let’s take a closer look.

Okay, so they look kind of like dandelions. Let’s apply the key:

- Toothed/lobed leaves? No. I can’t even tell whether there are any leaves attached to these things, but they’re certainly not large with toothed edges.

- Basal rosette? No. Again, I don’t see leaves at all, and I certainly don’t see a basal rosette pattern.

- Yellow flowers? Yes. Thick hollow reddish/purplish flower stem that breaks easily and has milky sap? No. Look at that big tall center flower and its obviously green stem. Its stem is also whiplike and strong.

- Taproot? Unknown. If a plant has failed the earlier tests, leave it alone. No need to kill it just to check its roots.

So I’m gonna go ahead and say this one isn’t a dandelion, because it fails several points of our tests. I think they’re actually some Asteraceae relative, if memory serves.

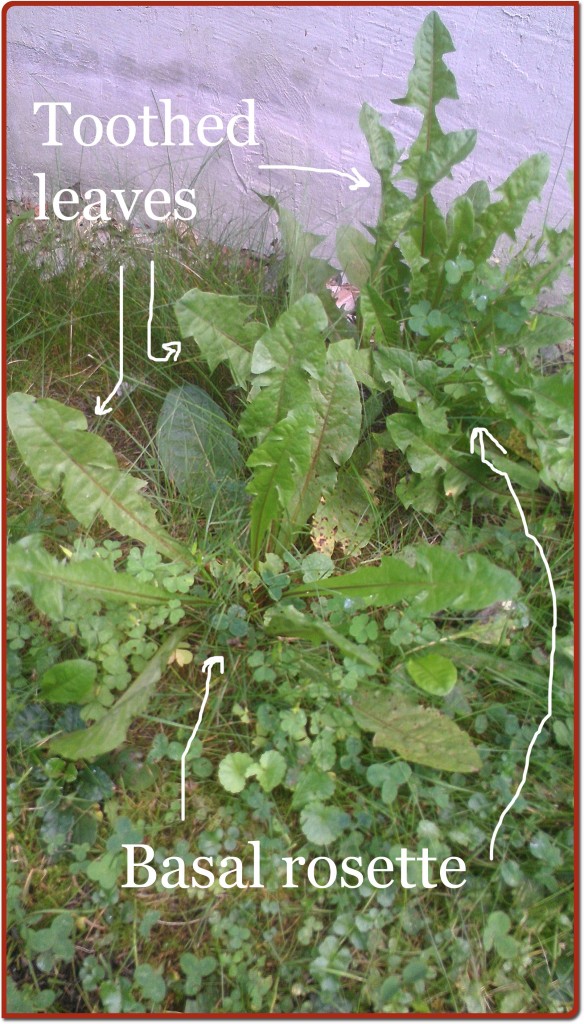

What about these?

Looks like a dandelion to me. Let’s check.

- Toothed/lobed edges? Yes. Both of the large plants in this picture have leaves with in-cut edges. They’re a bit different from each other; genetic drift is like that. But these both pass the toothed-edge test.

- Basal rosette? Yes. Do you see how all the leaves tend to issue from a central point, as if they’re clustered around in a circle? That’s what a basal rosette is*.

- Yellow flowers? No, but there aren’t any other kinds of flowers either. Thick hollow reddish/purplish stem that breaks easily and has milky sap? No, but there aren’t any flower stems.

- Taproot? Yes. If we dug these up, we’d find that they had taproots that looked kind of like this one:

At this point, I’m pretty confident calling this a dandelion.

Final thoughts

If you’re not confident about your plant identification, use common sense: don’t eat that plant. Ask someone who knows, or compare against known samples.

You can look up Taraxacum officinale, the scientific name for the common dandelion, and you’ll find tons of pictures. Or you can look for videos. You can learn to use a dichotomous key, which is a botanical tool for characterizing plants by the ways they differ from each other. The short checklist I gave above is an example.

This checklist is the one I use in identifying dandelions to use in making dandelion tincture. I hope it helps you!

If you’re confused or want more pictures, check another source before you go eating wild plants. Here are some good ones.

*Random factoid: basal rosettes are thought to have evolved as a defense against grazing animals, since their lack of main stems and low-to-the-ground habit make them harder for a cow or sheep to get their teeth around and destroy the whole plant. They might lose some leaves, but the plant survives.

3 thoughts on “Identifying Dandelions in Autumn”