Pathologizing Language

Most of you have seen the video about the Crazy Nastyass Honey Badger, with narration by Randall, somewhere in your travels around the internet. I delight in using the honey badgers to teach about crisis hotlines; we’re using the honey badger in our initial training to talk about inappropriate sexual callers, frequent callers, the virtues of directness, etc.

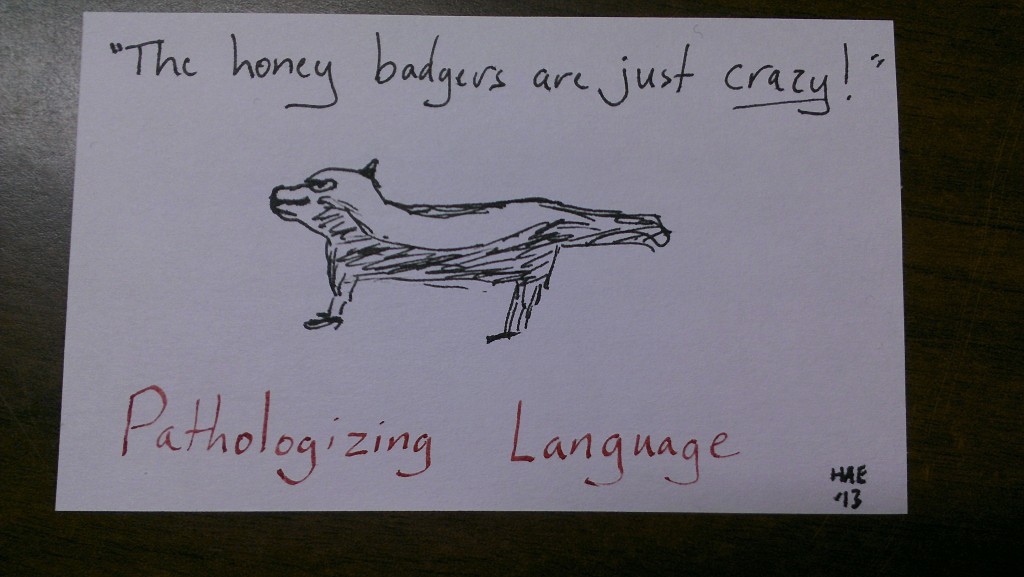

Today I’d like to talk about language. At one point, Randall says “Oh, the honey badgers are just crazy!”. There could hardly be any moment more germane to start our discussion of pathologizing language.

What is pathologizing language?

I’m thrilled that you asked. It’s judgmental language that examines someone’s behavior and ascribes a pathological cause to it. In plainer English, pathologizing language assumes that others are the way they are because they’re sick, and (by inference) makes the sickness seem like the most important thing about the person.

“The honey badgers are just crazy!” labels the honey badger with a mental illness and basically says that you don’t need to know anything else about them–they’re just crazy; what else is there to know? It’s a label that puts the honey badger in a box and assumes that we, the outside observers, are capable of knowing exactly what is going on for the honey badger and why it behaves the way it does.

We might just as fairly say that honey badgers are highly adapted predators with little fear of pain. They’re courageous and resourceful, fierce and dangerous. They’re really good at doing what comes naturally for them: being total badass predators you would not want to meet in a dark alley.

But that’s not the same as being crazy. When we call them crazy, we’re using a stigmatizing term from our experience that makes their natural behavior (badass predator mode) seem like an illness or like there’s something wrong with them. That’s pathologizing language.

Examples of pathologizing language

People often use pathologizing language as part of an ad hominem attack designed to undermine a person’s credibility or standing. By associating another person with something we find undesirable or sick, we subtly damage the other person. Often we include minimizers like “just” or “only” to help the knife sink even deeper.

- “She’s just a crazy person”

- “Yeah, he’s an alcoholic, what do you expect?”

- “Oh, she’s PMSing again, it’s always like this around this time of the month”

- “Stop acting so gay”

- “Just another entitled homeschooler”

- “You’re just suicidal”

- “Of course he has health problems… he’s fat”

- “I mean, she’s an engineer. Why were you expecting empathy?”

- “She’s such a drama queen”

- “We got another whiny schizophrenic on line 2”

In each case, we’re applying a label and using it to minimize and disrespect how the other person is feeling. We also make it seem as though the person’s behaviors and feelings are due to some problem that we’ve identified. We’re assuming that we know why the person is doing what they do, and are therefore writing it off. That’s the real problem with pathologizing language: it covers up disrespect and allows us to pigeonhole people and forget about them.

What if there really is a problem we need to discuss?

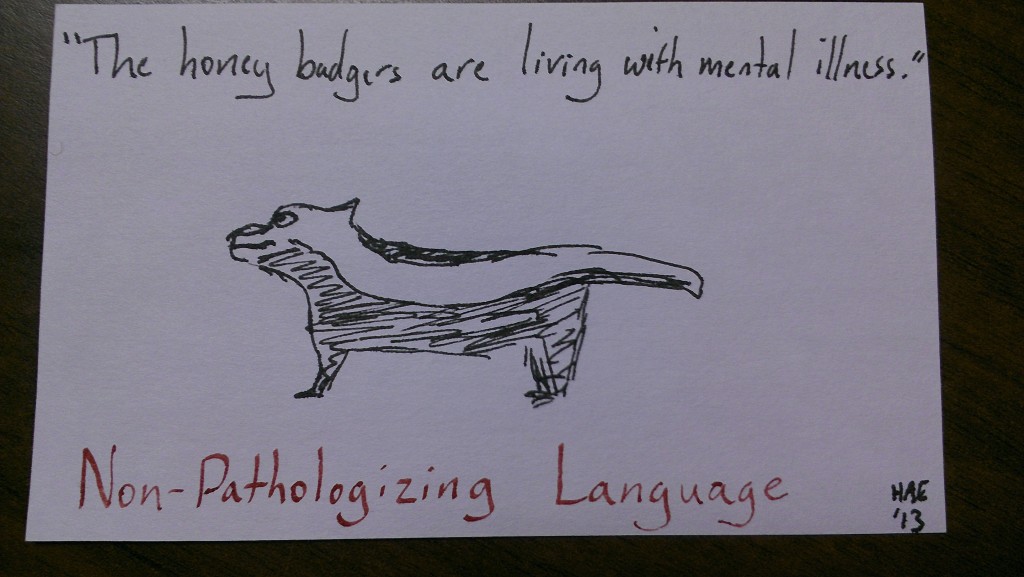

Sometimes we still have to talk about stuff, and sometimes people really do have mental illnesses, suffer from addictions, or behave in ways that society has decided are inappropriate. When that’s the case, use non-pathologizing language wherever possible.

What’s non-pathologizing language? It’s not making assumptions about what causes a person’s behavior, not pigeonholing them, and not claiming that you can know everything about a person just because you know some labels for them.

This can be subtle; here are some examples:

- The honey badgers are just crazy. (pathologizing and belittling)

- The honey badgers are mentally ill. (pathologizing; defines what the HBs are)

- The honey badgers have mental illnesses. (less pathologizing; reports the fact but not as the only thing about them)

- The honey badgers are living with mental illness. (less pathologizing; reports the fact but draws attention away from it)

- The honey badgers suffer from compulsive behaviors. (even less pathologizing; reports what they do, in a compassionate way)

- The honey badgers hunt cobras even when they aren’t hungry, and they seem unable to stop. (even less pathologizing; focuses almost totally on what they do.)

More?

- Mrs Honey Badger is PMSing again. (pathologizing)

- Mrs Honey Badger seems very angry today. (non-pathologizing)

- I wish Mr Honey Badger would stop acting gay all the time. (pathologizing)

- I get confused and uncomfortable when I see Mr Honey Badger looking for new cobra recipes in cooking magazines. (non-pathologizing; gets at the root of the speaker’s concern)

We could go on, but in general:

- Describe what you see, not what you think it means. If someone is talking to people who aren’t visible to you, say that–there’s no need to say it’s because they’re crazy or because they’re schizophrenic.

- Talk about behavior, not what you think caused it.

- Beware of using language that minimizes other people’s experiences or encourages them to be silent.

- Recognize that what you think is aberrant and sick may just be normal behavior for other people. Stay open to that possibility.

The honey badgers get sad when people call them crazy. They’re just trying to be themselves, working their way through a confusing and changing world that’s full of cobras and jackals that steal their mice and call them stupid.

6 thoughts on “Pathologizing Language”